The Australian federal government has revealed its proposed plan for Artificial Intelligence regulation and the moment has not arrived too soon.

At stake are hundreds of thousands of new jobs, savings to the economy expected be valued at over $100 billion and a boost to GDP valued at up to $600 billion. It could also deliver unprecedented improvements in healthcare delivery and a powerful tool in the battle against climate change.

However, Artificial Intelligence is failing to win community trust, slowing its adoption. This is in part due to well publicised cases in which lawmakers have struggled to deal with negative impacts of AI, including on mental health, consumer protection, human rights, the safety of children and even the political processes that influence legislation.

It’s clear that the Australian government has been following all these developments in AI closely and it seems particularly concerned about negative impacts of inherent racial bias in AI systems.

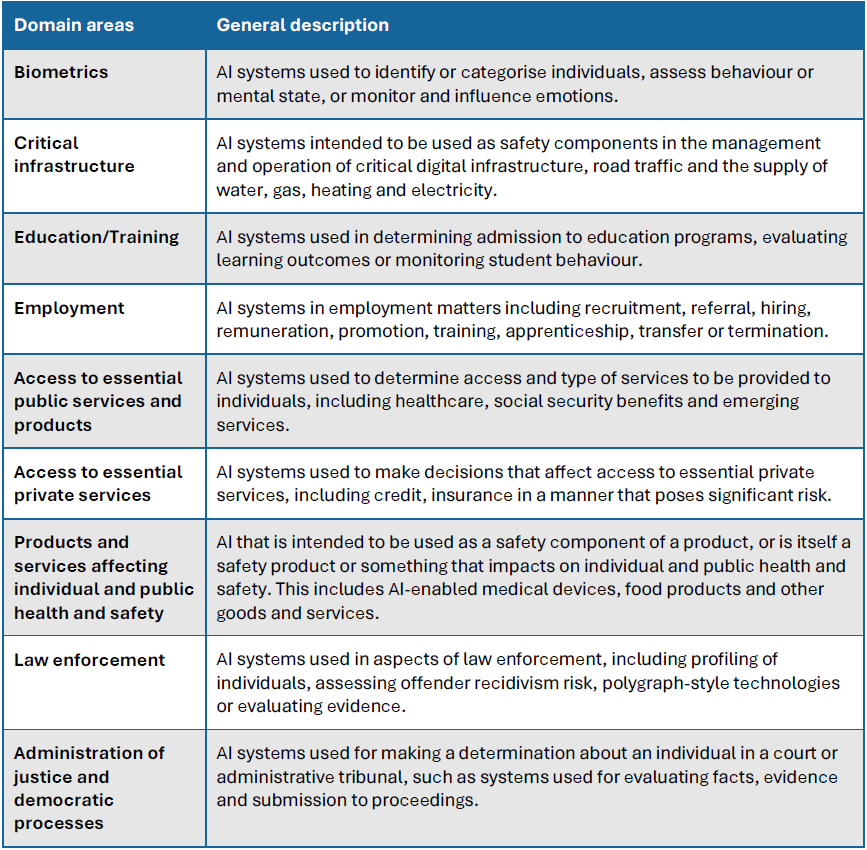

This week the government released its proposals paper for Artificial Intelligence regulation. The paper builds on the government’s interim response and proposes “guardrails” for AI systems designated to be “high-risk”, such as those used in HR applications and criminal justice settings.

Looking overseas

Following a familiar pattern when it comes to technology regulation in Australia, the federal government has waited to see how other countries with similar economic and political features are approaching Artificial Intelligence regulation.

This is not necessarily indicative of lack of leadership from the government. Most investment in advanced technology development occurs outside of Australia and this is particularly true in the case of AI. Accordingly, it makes sense to harmonise Australia’s Artificial Intelligence regulation with our main technology trading partners. It avoids reinventing the wheel with unnecessary regulatory duplication.

This will harmonise our domestic AI technology innovation environment with those fostered offshore.

Also, while some of the challenges that AI poses are universal, some are unique to nation states which, like our own, place a high value on democracy and civil rights. As the government wrote in its proposal:

“…it shouldn’t be a surprise to find that our regulations will follow patterns that are similar, if not identical to those observed in the US, Europe, the UK and Canada. They’re similar to Australia, economically, politically and socio-culturally and thus face many of the same challenges.”

So, what is the Australian government’s proposed approach to Artificial Intelligence regulation?

The government prefers to focus on a harm prevention model; a risk-based regulatory framework that aims to stop AI-related catastrophes before they happen. The government proposes to do this with mandatory guardrails for what it describes as “high-risk AI”.

The government’s plan for Artificial Intelligence regulation designates systems as high-risk if they fall into two broad categories:

- AI systems and General-Purpose AI (GPAI) models where risk is foreseeable due to their functionality and/or the settings in which they’ll be applied

- GPAI models where risks less foreseeable but considered inherently risky due to the strength of their capability

The approach, it says, is to ensure that low risk AI innovation is not unnecessarily hindered by rules and red tape.

The guardrails for high-risk Artificial Intelligence

The government proposes to regulate high-risk Artificial Intelligence with ten “mandatory guardrails” summarised below:

- Establish, implement and publish an accountability process including governance, internal capability and a strategy for regulatory compliance

- Establish and implement a risk management process to identify and mitigate risks

- Protect AI systems, and implement data governance measures to manage data quality and provenance

- Test AI models and systems to evaluate model performance and monitor the system once deployed

- Enable human control or intervention in an AI system to achieve meaningful human oversight

- Inform end-users regarding AI-enabled decisions, interactions with AI and AI-generated content

- Establish processes for people impacted by AI systems to challenge use or outcomes

- Be transparent with other organisations across the AI supply chain about data, models and systems to help them effectively address risks

- Keep and maintain records to allow third parties to assess compliance with guardrails

- Undertake conformity assessments to demonstrate and certify compliance with the guardrails

The government is seeking feedback from industry and stakeholders on whether guardrails should be removed or added from its list of measures. It’s also seeking feedback on its principles for designating AI systems (or models) as high-risk are sensible.

What’s considered “high-risk”?

While the government describes its proposed approach as a “framework”, it has articulated its principles for identifying AI considered high-risk well. This suggests its final approach will capture them all. It says:

“In designating an AI system as high-risk due to its use, regard must be given to:

- The risk of adverse impacts to an individual’s rights recognised in Australian human rights law without justification, in addition to Australia’s international human rights law obligations

- The risk of adverse impacts to an individual’s physical or mental health or safety

- The risk of adverse legal effects, defamation or similarly significant effects on an individual

- The risk of adverse impacts to groups of individuals or collective rights of cultural groups

- The risk of adverse impacts to the broader Australian economy, society, environment and rule of law

- The severity and extent of those adverse impacts outlined in principles (a) to (e) above.”

Drawing on international examples for GPAI regulation

The government is seeking feedback on international approaches to defining high-risk GPAI models. For example, in the US, President Joe Biden issued an executive order imposing mandatory reporting requirements on suppliers of all GPAI models with capabilities above a defined threshold.

Canada and the European Union have gone further, requiring minimum regulations for all GPAI models. The Australian government appears to favour these latter approaches and is proposing to apply mandatory guardrails to all GPAI models.

“Since most highly capable GPAI models are not currently developed domestically, Australia’s alignment with other international jurisdictions is important to reduce the compliance burden for both industry and government and enables pro-innovation regulatory settings.”

It adds:

“Feedback is welcome on how mandatory guardrails should apply to GPAI models in Australia, and whether any further approaches should be considered, such as where a sub-set of guardrails or different guardrails might be needed.”

Less gigaflops good?

Interestingly, the proposal paper posits another possibility for assessing GPAI risk based on processing power. It asks of stakeholders:

“What are suitable indicators for defining GPAI models as high-risk? For example, is it enough to define GPAI as high-risk against the principles, or should it be based on technical capability such as FLOPS (e.g. 10^25 or 10^26 threshold), advice from a scientific panel, government or other indicators?”

One imagines the likes of Nvidia, Intel and other chip fabricators will be taking note.

The government has given stakeholders a deadline of October 4 to lodge submissions in response to the proposals paper.

Industry response

There have been few industry responses to the proposals to date. Business Council of Australia Chief Executive, Bran Black, said that the paper was a “step in the right direction”. However, he expressed concern that any new Artificial Intelligence regulation may lead to duplication of existing laws and place an excessive compliance burden on Australian

businesses.

“Our existing regulations already address many of the potential challenges AI may cause if it is used maliciously,” Mr Black says.

“We acknowledge the need for a regulatory framework with respect to AI, but we should reject the idea that more regulation means better outcomes – ultimately it’s critical that we apply great scrutiny to any potential new regulations to ensure protections don’t unreasonably come at the expense of innovation.”

Somewhat predictably, technology industry body, Tech Council of Australia (TCA), welcomed the proposal paper. However, in its response, it took care to ensure it also addressed the release of the Department of Industry, Science and Resource’s voluntary standard, which coincided with that of the proposal paper.

“The Tech Council supports the release of the voluntary standard, as well as the proposals paper for mandatory safeguards for high-risk AI systems,” TCA chief executive Damian Kassabgi said.

“We see this as a crucial step in building an appropriately balanced regulatory strategy for AI governance to support confidence and responsible adoption in AI technologies”.

Is Artificial Intelligence in finance and accounting significant yet?

While there are barriers to adoption for AI in finance and accounting, the sector’s potential for exposure to high-risk Artificial Intelligence regulation is as high as that for any other knowledge-based service sector.

Sector-specific AI applications, such as rules-based tax decision-making, are already in production. So to are and machine learning systems for processing compliance information at scale.

AI is also being combined with other technologies such optical recognition to automate client data ingestion and business cases for Generative AI continue to be tested.

Generative Artificial Intelligence may soon be able to emulate human-like cognitive behaviours required identify clients with specific advisory needs. This could create opportunities for business development or even entirely new advisory products. However, as the old saying in computing goes: “garbage in, garbage out”.

These systems must be trained on accurate data and that’s far from guaranteed. Furthermore, they remain vulnerable to the algorithmic and systemic biases that have created ethical dilemmas in other disciplines such as human resources and justice administration.

The Boss Diaries’ view

The notion that a voluntary standard will win community trust in AI is optimistic at best.

While often dismissed as engaging in hubris, the Labor government has a record of taking a strident approach to digital policy. For instance, its willingness to use its powers under the Online Safety Act 2021 to issue Elon Musk’s X and Facebook owner, Meta, with takedown notices earlier this year. At the very least, it would appear that it doesn’t want to be perceived as having a tin ear when it comes to community concerns about unintended impacts of digital technologies.

If your business’s technology roadmap includes AI or machine learning systems, we recommend taking steps to ensure that your technology vendor or IT department has checked to see if their capabilities could fall within scope of the government’s Artificial Intelligence regulation plan. From there you need to asses how crucial these are to your future business plans.

If they are critical, you’ll need to devote resources to assessing their capabilities and the context within which you intend to use them. If they fall within the government’s threshold for high-risk or might be assessed as advanced, then you will need to make preparations to meet the mandatory guidelines and start taking steps to meet its reporting requirements.

Admittedly, the government isn’t being very clear about what capabilities are in scope for mandatory guardrails at this stage. We recommend contacting the government to find out as much as detail as you can to inform your decision making process. Specifically, try to discover if the government is particularly concerned about capabilities that you can reasonably foresee being applicable (or integral) to your technology roadmap.

The Labor government isn’t shy of making outlandish promises to regulate the digital realm and you should make your voice is heard if you think it’s being unrealistic.